Prior to the CrowdStrike outage, 2024 was already well on its way to becoming the Harvey–Irma–Maria year1 of Systemic Dependency Risk with the Change Healthcare ransomware attack in February and CDK Global ransomware attack in June, as well as the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse and resulting Port of Baltimore closure in May. While Change Healthcare and CDK Global impacted very different industries – healthcare services and automotive dealerships, respectively – they have in common some very important features for understanding Systemic Dependency Risk, and will together be the subject of this latest installment of our ongoing series of case studies.

Change Healthcare

UnitedHealth’s Change Healthcare subsidiary grew from a healthcare technology startup (or startups)2 into a giant in the healthcare “Revenue Cycle Management” (RCM) space over the first two decades of the millennium. Somewhat uniquely to healthcare, RCM is the set of tools and processes that facilitate healthcare providers and hospitals getting paid for the services they provide to patients. Apologies in advance for descending into the weeds on this, but it’s necessary in order to understand how Change Healthcare became such a critical dependency in an industry that represents 17.6% of US GDP.

There are two reasons that RCM is so significant for the healthcare industry:

- The bulk of payments for healthcare services come via third parties (health insurers and government plans), rather than directly from their customers (patients)3.

- The coding of claims for healthcare services reimbursement is byzantine4. Inaccurate or incomplete coding can result in claims being rejected by payers.

RCM includes many different services, including “eligibility and benefits” checking to ensure that a patient’s healthcare plan info is valid and to determine copayments and deductibles, “claims editing” to correct coding that might result in rejection, remittance tracking and posting, etc. The whole multi-step, multi-party healthcare payment system has the unnecessary complexity of a Rube Goldberg machine and is only slightly less comically surreal. RCM tools and services don’t so much aim to solve the problem as to optimize revenue yield and efficiency within the system.

At the heart of most of these RCM services are Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) transactions transmitted from providers to payers and vice versa. Transitioning healthcare claims from paper via mail or fax to EDI transactions in the 1990s and early 2000s was an obvious win for RCM technology, saving labor, paper and postage costs. It also dramatically reduced the time between rendering healthcare services and receiving payment, liberating a lot of tied-up working capital in the healthcare system.

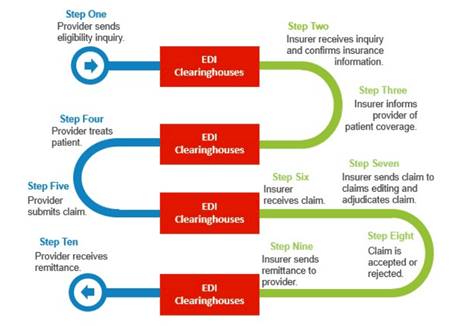

Because of the complexity for each provider arranging electronic connections to each payer with their specific format and coding requirements, RCM has grown around an obscure utility in the healthcare industry: EDI clearinghouses. The US Department of Justice in their objection to UnitedHealth’s acquisition of Change Healthcare (more on this in a moment) provided the diagram below to emphasize the criticality of EDI clearinghouses in the healthcare RCM transaction flow:

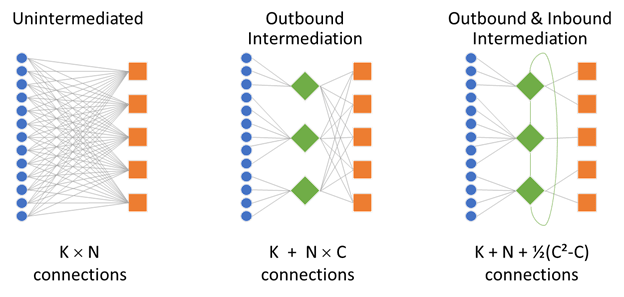

Each provider connects to an EDI clearinghouse which routes the EDI transaction to the payers. In fact, many payers also arrange with an EDI clearinghouse to manage their inbound transactions, such that a transaction might go from a provider to their EDI clearinghouse and then to the payer’s EDI clearinghouse en route to the payer. Where there are many providers and many payers, there is an obvious efficiency to this intermediated network arrangement in terms of reducing the number of pairwise connections, and this favors consolidation and scale for EDI clearinghouses:

This tendency of networked technology solutions to evolve into critical dependency nodes will be a recurring theme for Systemic Dependency Risk across many different industries and business processes.

Change Healthcare has by far the biggest EDI in the industry, claiming in 2020 to process over 15 billion transactions and $1.5 trillion of claims annually… that’s over 30% of annual US healthcare spending and over 40% of the estimated industry total of 34.5 trillion electronic transactions in 2020. The US Department of Justice merger objection noted that more than half of all commercial payer medical claims went through Change Healthcare. When the government is alleging anti-competitive threats due to excessive market concentration and vertical integration with underlying industry-wide technology infrastructure, that should be a strong clue about potential Systemic Dependency Risk.

So, it was huge news when Change Healthcare experienced a ransomware attack on February 21, 2024. For most of the public, the headline was the size and scope of the data breach: personal identifiers and health information for over 100 million individuals (subsequently revised upwards to 190 million). But it was also extremely disruptive to the US healthcare system when Change Healthcare shut down its services in response to the hack. Healthcare providers who used Change Healthcare’s clearinghouse began “hemorrhaging money” as they were no longer able to process claims and receive revenue for the services they provided. Many experienced disruption even if they used a different clearinghouse because some transactions were submitted to payers that used Change Healthcare for inbound transactions. Major health insurers other than UnitedHealth saw 15-20% reductions in submitted claims volumes, though that was presumably to their benefit (other than a headache for their actuaries doing reserving analyses).

In addition to not being able to process claims, healthcare providers were unable to perform Eligibility & Benefits and Prior Authorization checks to determine the patient’s insurance coverage and any copayments or deductibles prior to providing services. Without this step, providers may have failed to collect amounts owed by patients and/or been unable to schedule non-urgent services which created real losses, as opposed to the cash flow timing problem from inability to process claims (assuming claims would eventually be processed once systems were restored).

The full magnitude of healthcare industry cash flow disruption is difficult to estimate, but the scale was enormous. The Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association reported losses of over $24 million revenue per day from a survey of just 12 of its member hospitals. The American Hospital Association surveyed nearly 1000 of its member hospitals and reported that around one-third had impact of more than half their revenue, and around half had revenue impact of $1 million per day or greater. Some back-of-the-envelope math: with aggregate annual hospital revenues of approximately $1.5 trillion, that’s $4.1 billion revenues per day, and if around 30% went through Change Healthcare’s clearinghouse, that’s a $1.2 billion per day cash flow problem.

Most hospitals and health systems maintain substantial cash balances as a buffer to short-term disruptions. A 2022 study of non-profit hospitals with S&P credit ratings found an average of 218 days cash on hand, with only 9% rated below “adequate” with less than 110 days cash on hand (or 100 days for multi-hospital health systems). Three large publicly-traded healthcare systems reported only “transitory” disruptions. Some health systems were able to switch clearinghouse vendors, with Change Healthcare’s biggest competitor Availity quickly stepping in to offer free “lifeline” service.

Physician practices were far more vulnerable due to less robust cash reserves and/or credit facilities, and less agility in switching clearinghouses or engaging in other workarounds. The American Medical Association conducted physician surveys in late March and late April of 2024 which reported dire consequences: widespread loss of revenues and additional staff expenses, missing payrolls, dipping into personal funds to cover practice expenses, and a number of anecdotes worrying of impending bankruptcy. More back-of-the-envelope math: $978 billion of aggregate annual revenue for physician and clinical services is $2.7 billion per day, of which around 30% impacted by Change Healthcare’s outage works out to about an $800 million per day cash flow problem.

UnitedHealth quickly set up a “Temporary Funding Assistance Program” on March 1, 2024 to provide interest-free loans to practices whose cash flows were disrupted in hopes of alleviating some of the liquidity issues. These loans quickly ballooned to $3.9 billion as of March 31, 2024 and $6.5 billion as of April 30, 2024, and continued to rise to $8.1 billion as of June 30, 2024 and ultimately $8.9 billion gross and $5.7 billion net of repayments as of September 30, 2024… repayments have continued slowly5.

UnitedHealth hoped to bring the clearinghouse functions back online by the middle of March 2024, three weeks after the attack. This proved to be overly optimistic, particularly re-establishing connections with payers. Many of Change Healthcare’s core services were nearly back to normal by April 22, 2024 – two months after the attack– but it wasn’t until November 19, 2024 – almost nine months after the attack – that all services were fully restored.

While the cash flow impacts were potentially catastrophic – probably many tens of billions of dollars for the industry – they were transitory and partially mitigated by UnitedHealth’s interest-free loan program6 and switching to other clearinghouses. It’s far more challenging to estimate the non-transitory real costs: paying staff overtime to manually submit via paper or fax, cost to setup alternative clearinghouse arrangements, uncollected copayments, procedures not performed and/or claims denied for lack of Prior Authorization, etc. One way to put an order of magnitude on it is to look at the savings achieved by the healthcare industry’s adoption of electronic transmission. The Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare estimates that the average cost of manual transactions is more than double that of electronic transactions, generating $160 billion of annual cost savings for providers and payers at current industry adoption rates. To put a rough upper bound on the cost, we can suppose that extra costs and frictions during the Change Healthcare outage were similar to the cost savings from avoiding manual transactions for the fraction of transaction volume impacted by the outage, around 40%: that works out to around $5 billion to $10 billion for the outage lasting several weeks to two months.

Incident Summary

Change Healthcare Ransomware Attack – February 21, 2024

| Source of disruption | Transaction Interchange | |

| Root cause | Ransomware | |

| Scope of impact | Geographic | US |

| Industries | Healthcare | |

| Estimated revenue | $5 billion per day7 | |

| Duration | 1 -2 months | |

| Estimated losses | Economic | $5 – 10 billion |

| Insured | None (?) | |

| Known losses | None | |

CDK Global

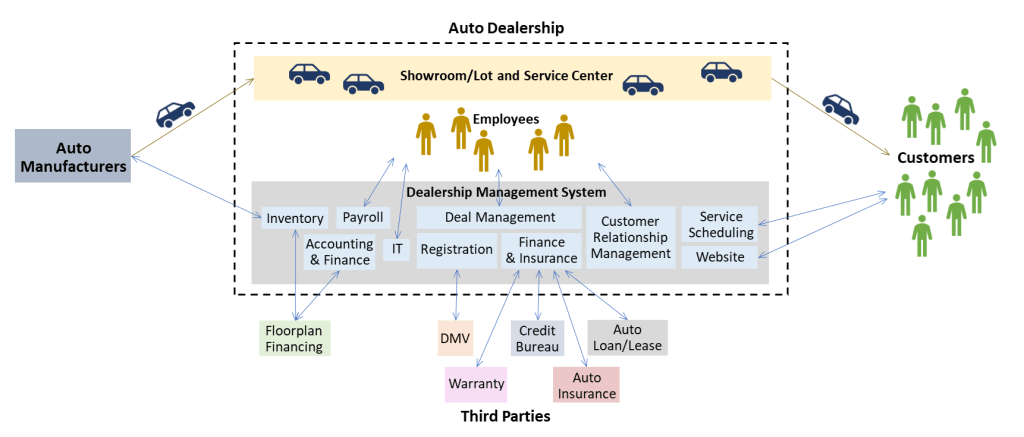

CDK Global is the dominant player in Dealer Management Systems (DMS)8, which is a mission-critical technology suite that includes accounting, payroll, vehicle inventory, customer relationship management, financing and insurance, service scheduling and parts inventory, website / digital marketing, and in some cases full IT outsourcing as a Managed Service Provider9. In parallel but in contrast to the straightforward physical flow of cars from manufacturer to dealership to customer, the DMS handles an intricate collection of electronic transactions that enable car sales in the context of the modern business model of an auto dealership.

While the scope of DMS is much broader than Revenue Cycle Management in healthcare, there are some key similarities in the networked intermediation between auto manufactures and dealers, as well as between dealers and the auto finance ecosystem (credit bureaus, banks, and insurers)… and ultimately the greatest resemblance of all: without their DMS, car dealers would have to revert to the manual processes of the previous century.

When CDK Global had to shut down due to a ransomware attack on June 19, 2024, it threw auto dealerships across the country into chaos. Manual processes for new sales were inefficient and slower. Information on in-process deals was inaccessible, so the sale was either delayed or lost. Basic administrative functions like payroll were impacted.

The impact of not being able to sell cars is a bit tricky: if the customer’s purchase is merely delayed, the impact to the dealer might only be the additional interest expense on floorplan loans financing their vehicle inventory; however, if the customer goes to a different dealer, the sale is lost permanently. In either case, the dealer continues to incur the cost of operating their business – real estate expense, staff expense, etc. – during the delay.

It’s particularly worth noting that auto dealerships have evolved a business model where the two most important operations are (1) repair and maintenance services and (2) dealer incentives on financing and insurance10. Financing and Insurance is obviously mutually interdependent with sales, but far more difficult to revert to manual processes when it comes to things like credit checks, lender offers, loan and lease payment calculations, etc. Parts and service is not immediately dependent on sales, but also has significant systems dependence for scheduling, parts inventory, customer account management and payments.

CDK Global’s core DMS services began to be restored for some large customers in the second week following the incident11, with full restoration in week three12. However, even with CDK Global’s systems fully operational, the full capability of the network continued to recover slowly as auto manufactures and other third parties in the ecosystem reconnected13.

One expert estimated the economic impact at $1.02 billion, including lost earnings on car sales, additional interest expense on floor plan loans, lost earnings on parts & service, and additional staffing and IT costs. All six of the large publicly-traded dealership groups – collectively representing almost 10% of the industry’s new car unit sales volume – reported that their sales volumes were negatively impacted by unavailability of their CDK Global DMS, three of which providing quantitative estimates of the overall impact:

| Estimated Impact | % of Annual Revenues | Additional Notes | |

| Asbury Automotive Group | $19 million to $23 million ($0.95 to $1.15 per share) | 0.12% | Cyber insurance limit of $15 million after $2.5 million deductible… no info as to whether this claim was successful. |

| Sonic Automotive | $47.2 million | 0.41% | Includes $13.4 million additional expense for commission-based staff |

| AutoNation | $71 million ($1.75 per share) | 0.34% | Includes $43 million additional expense for commission-based staff |

Also note: Group1 Automotive reported $5.9M one-time expense for sales staff compensation, and also noted that they had recognized a $10M recoverable for business interruption insurance(!)

The above three dealership groups collectively represent 4.2% of the industry’s annual unit sales volume… extrapolating their $140 million aggregate loss to the entire industry, assuming CDK Global has 40-50% of the DMS market share, gives an estimate of $1.3 billion to $1.7 billion losses.

Incident Summary

CDK Global Ransomware Attack – June 19, 2024

| Source of disruption | Software-As-A-Service / Managed Service Provider / Transaction Interchange | |

| Root cause | Ransomware | |

| Scope of impact | Geographic | Primarily US |

| Industries | Auto dealers, and to a lesser extent upstream (auto manufacturers) and downstream (online marketplaces, auto lenders) | |

| Estimated revenue | $1.3 billion per day14 | |

| Duration | 2 – 3 weeks | |

| Estimated losses | Economic | $1.0 – $1.7 billion |

| Insured | ≪$100 million | |

| Known losses | • AutoNation: $71 million • Sonic Automotive: $47 million • Asbury Automotive Group: $19 – $23 million • Group1 Automotive: at least $10 million | |

| TOTAL: at least $150M | ||

Lessons learned

1. Systemic Dependency Risks can come from unexpected places

As with the CrowdStrike incident in the previous case study, one of the biggest lessons is to look beyond the traditional supply chain for dependency risk. Both Change Healthcare and CDK Global were fairly obscure to the general public, but should have been well known in their respective industries. They likely would have shown up on vendor lists, and featured heavily in IT integrations and approvals. Yet they might not have been on the radar for supply chain risk because they’re not suppliers in the traditional sense of goods and services. And there’s also an issue of focus on the bigger, more important issues: medical care operations have a high-reliability requirement, and RCM isn’t strictly required to provide care. Car sales tend to focus on the heavy, expensive tangible objects physically present on the dealer’s lot. To find these more subtle dependencies outside of the “core” product/service delivery chain, you almost have to trace in reverse from the revenue. Dependency risk – or supply chain in the broadest sense – includes *all* the inputs required for your product or service to produce revenue.

2. Value of diversity in commercial ecosystems

Another repeat from the CrowdStrike case study: it is simply not healthy for critical functions in any given industry to have dominant players with nearly 50% market share. The criticality of both Change Healthcare and CDK Global should not have been a surprise, as both were involved in US government anti-trust objections that noted their dominant market shares. Scale and network effects in transaction interchange and technology businesses tend to lead to these types of concentrations. Insurance could play an important role in price-based self-regulation if business interruption policies for Systemic Dependency Risk existed, and would be a much more attractive option than regulation.

3. Lenders and Investment Managers should think about Systemic Dependency Risk with respect to sector concentrations

The Change Healthcare outage particularly constricted cash flows for thousands of independent physician practice groups and smaller non-profit healthcare systems and hospitals. And had the duration of the CDK Global outage been longer, it could have caused similar cash flow problems for thousands of auto dealerships, most of which are privately-owned and range in size from just a few stores to dozens across multiple states15. Banks specializing in lending and financing solutions for these sectors could have seen spikes in default rates16.

Other industries may have more significant share in publicly-traded companies where a Systemic Dependency Risk event could potentially impact earnings across a sector in an equity portfolio. There’s also the risk that knock-on effects bleed out of a narrow sector like auto dealerships, and into adjacent broader sectors like auto manufacturing and auto finance.

From a portfolio management perspective, Systemic Dependency Risk means that “correlation” within industries may be higher for extreme downside events than when (under-) estimated over periods without such events.

4. Ransomware and contingent business interruption under cyber risk insurance policies

Both the Change Healthcare and CDK Global outages had their root cause in ransomware attacks, which have become increasingly prevalent over the past decade. Given the intersection of Systemic Dependency Risk and technology solutions, it’s fair to suppose that ransomware is likely high among the leading underlying causes of Systemic Dependency Risk.

Cyber risk insurance policies generally cover the policyholder for business interruption if it’s caused by an attack on their systems. Policies may also cover business interruption caused by third-party systems used by the policyholder becoming unavailable due to an attack on that third-party (sometimes worded as “Dependent Systems Failure” coverage), but typically with much lower sub-limits and/or exclusions.

It’s unlikely that healthcare providers inability to submit EDI transactions to the Change Healthcare clearinghouse would meet definitions for business interruption coverage under cyber risk insurance policies, though some of Change Healthcare’s other RCM solutions may have been offered as on-premises software or Software-as-a-Service resulting in partial coverage. The CDK Global case is a bit likelier for cyber risk insurance coverage because of its more direct role as a Software-as-a-Service and sometimes also as Managed Service Provider, and indeed at least one auto dealer (Group1 Automotive) recognized an insurance recoverable.

But in general, Systemic Dependency Risk caused by ransomware attacks will only be covered as contingent business interruption under cyber risk insurance in a subset of cases where the third-party dependency meets the definitions under the policy wording, and even then subject to sub-limits and exclusions that may limit the effectiveness of coverage. Cyber risk insurance certainly will not help with non-technological dependencies that are interrupted by cyber attacks (e.g. the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack and the Schreiber Foods ransomware attack, both in 2021). And obviously ransomware is only one of many potential causes that could disrupt a critical dependency.

So from a Systemic Dependency Risk management perspective, you might get lucky and find you have some coverage from your cyber risk insurance policy, but counting on luck is obviously not an acceptable risk management approach.

- Or for old timers like me, Katrina-Rita-Wilma from 2005. ↩︎

- It’s a somewhat complicated corporate history: Change Healthcare itself began in began in 2007 as a technology platform for healthcare plan cost transparency and consumer engagement. In 2014 it was acquired by Emdeon, with the combined entity taking the Change Healthcare name. Emdeon, formerly known as WebMD prior to spinning off its namesake consumer-facing online healthcare information business in 2005, had become a healthcare business-to-business technology juggernaut with a string of more than a dozen acquisitions beginning with Healtheon in 1998. Then in 2016 the newly re-branded Change Healthcare merged with the Technology Solutions businesses of McKesson, one of the largest medical supplies and pharmaceuticals distributors to the US healthcare system, roughly tripling its size. And then in 2021 Change Healthcare was acquired by UnitedHealth and merged with the healthcare technology businesses in its Optum Insight subsidiary. ↩︎

- Even copayments and deductibles collected from patients are determined by their healthcare plans. True self-pay is mostly limited to cosmetic procedures and the uninsured. ↩︎

- Each claim requires one or more diagnosis codes and one or more procedure codes, potentially with modifier codes, in addition to the provider and facility information, patient information and healthcare plan numbers. The ICD-10 classification system contains over 69,000 diagnosis codes and over 72,000 procedure codes. ↩︎

- $1.2 billion in Q4 2024 to bring the net balance to $4.5 billion at year-end, and another $0.9 billion in Q1 2025. ↩︎

- Note that unsubmitted claims generated excess cash relative to claim cost projections for UnitedHealth and other payers, offset by an increase in reserves. Passing that excess cash on to providers as interest-free loans is essentially equivalent to just paying the expected claims in advance of submission. ↩︎

- $4.5 trillion annual US healthcare spend, 40% through Change Healthcare. ↩︎

- CDK has its origins in the early days of computerization with a couple of companies providing accounting and inventory management systems for auto dealers that ADP acquired in 1973. Over many years (and many acquisitions) following, the ADP Dealer Services division had evolved into a much bigger and broader Dealer Management Systems provider, before being spun off as CDK Global in 2014. When it tried to acquire a much smaller rival called Auto/Mate in 2017, the US Federal Trade Commission’s objection noted that the resulting combination would have 47% market share. ↩︎

- Somewhat ironically, CDK Global in particular touted cybersecurity as a key feature of its MSP services. ↩︎

- For the six large publicly-traded dealership groups – AutoNation, Penske Automotive Group, Asbury Automotive Group, Sonic Automotive, Group1 Automotive and Lithia Motors – in aggregate, parts & service and financing & insurance segments respectively accounted for 42.7% and 25.5% of total gross profits in 2024, while new car sales and used car sales segments accounted for 21.5% and 10.3%. ↩︎

- Sonic Automotive reported core DMS restoration on June 26th, AutoNation on June 29th, and Group1 on June 30th. ↩︎

- Penske Automotive Group reported full restoration on July 2nd, Group1 on July 3rd, and Asbury Automotive Group on July 8th. ↩︎

- For example, Penske Automotive Group noted an additional impact from delay awaiting Daimler’s reconnection. ↩︎

- Estimated US auto dealership annual revenues of $1.1 trillion, with 40-50% affected by CDK Global. ↩︎

- The market is still quite fragmented: the 150 largest dealerships still only account for around one quarter of the industry’s volume. ↩︎

- Hospitals and healthcare systems also represent about 7% of the municipal bond market. ↩︎

Leave a comment