“Unprecedented” feels like one of the most overused and abused words over the past 5-10 years that have seen quite a few severe wildfires and other natural disasters, a global pandemic, and more than a few political upheavals. No two disasters are exactly alike, so the most recent big one might be strictly speaking unprecedented. But in the more reasonable sense of similarity in nature and magnitude, calling our string of recent extreme events “unprecedented” betrays a lack of historical awareness and/or imagination.

It’s worth remembering that COVID-19 is more scientifically termed SARS-CoV-2, which is a strain of the original SARS-CoV-1 less than 20 years prior (not to mention the intervening MERS outbreak caused by another coronavirus from a different lineage within the same beta-coronavirus genus). And of course, we have very strong precedent for a global pandemic from the Spanish Flu just over 100 years ago.

The recent Los Angeles wildfires are also fairly well precedented by the 1991 Oakland Hills wildfire. The more recent event burned a much larger area (over 57,000 acres in LA vs 1520 acres in Oakland, both including substantial uninhabited areas), had more fatalities (30 vs 25) and destroyed many more structures (over 18,000 vs 3280). Even so, it’s not too hard to extrapolate from Oakland Hills wildfire to the LA wildfires – or even model – to foresee the potential risk of wildfire to cause substantial damage at the “Wildland Urban Interface” in a major metropolitan area.

We seem to be using “unprecedented” to more colloquially mean something very unexpected, something that the speaker hasn’t seen before or wasn’t expecting to see in their lifetime. But even if we allow that some events with plenty of precedent will be called “unprecedented”, we must be careful not to allow “unprecedented” to be an excuse for being unprepared for risks that have a reasonable chance of occurring.

As risk managers and modelers, we are trained to use history in order to inform our view of the improbable, using historical data to design and calibrate risk models and then using those models to extend probability measurements to extremes that are generally beyond a typical human lifespan (e.g. commonly used standards like 1-in-100, 1-in-250, 1-in-500 or even 1-in-1000)… but not too extreme! At some level of improbability, catastrophic events are so extreme that it’s not worth trying to manage to them. These extra-extreme scenarios would tend to cause such widespread devastation that companies would get government bail-outs or at least a “free pass” in comparison to their similarly devastated peers. In the most extreme scenarios, everyone would be dead anyway.

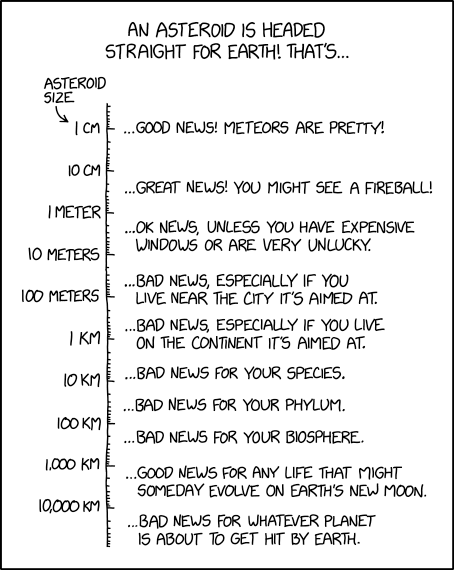

Asteroid 2024 YR4 made the news earlier this year when astronomers discovered it and determined that it will pass very close to Earth in 2032. On February 18th 2025, NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies estimated a 1-in-32 (3.1%) probability of it impacting Earth, though it has since been downgraded to no chance of striking Earth based on subsequent observations. 2024 YR4 has an estimated width of 55 meters with a range of 40 meters to 90 meters1. For reference, the 1908 Tunguska Event which flattened about 830 square miles of Siberian forest is estimated to have been 40 meters wide, while in 2013 the Chelyabinsk meteor at approximately just 20 meters wide caused glass breakage in more than 7000 buildings over an area of around 2500 square miles.

So Asteroid 2024 YR4 is in the “city-killer” category, were it to hit a city (see helpful guide to right). With this level of potential severity, and at the original higher levels of probability, it briefly rated a “3” on the 1-to-10 international Torino scale for near-earth object risk classification, which is in the yellow “meriting attention by astronomers” zone; if it had become near-certain to hit Earth, it would have rated an “8” (the lowest of the three ratings in the red zone where significant destruction is possible or likely).

Ironically, an asteroid impact has always been the go-to example of the scenario so extreme that risk managers and modelers don’t need to worry about it2. That’s definitely true of asteroids bigger than the “city-killer” class, up to and including the extinction event class: no sense trying to buy insurance to cover a scenario where you and your company – as well as the insurers you’d be hoping would pay the claim – would be dead.

But should risk managers have worried about Asteroid 2024 YR4, and should they worry about other future potential “city-killer” asteroids? Keep in mind that the earth is big – 197 million square miles of surface area – and 71% of that surface area is water. Much of Earth’s land surface area is unhabitable mountains and deserts; estimates of the inhabited portion vary but are typically around 10-15% of the land surface area. If an asteroid hits Earth, the most likely outcome is that it impacts over water or mostly uninhabited land, as was the case with Tunguska. We might perhaps conservatively suppose there is a 1-in-20 chance that a “city-killer” class asteroid actually does “city-killer” scale damage, conditional on striking Earth in the first place3. Combining that with a 1-in-32 chance of Earth impact would yield a 1-in-640 chance of catastrophic damage, right on the fringe of risk thresholds that risk managers worry about. Perhaps you might factor that down even more to account for the chance that it hits a city but not one where your company has people and assets, but then again, even without a direct hit there would probably have been a good chance of a disruption to something in your supply chain and/or revenue cycle4.

If another asteroid actually becomes a meaningful threat to hit Earth, will people say it was “unprecedented”? …probably, but they shouldn’t.

So why does this matter for Systemic Dependency Risk? Most of the systemic dependency risk events we should be worrying about will also be “unprecedented” given that we haven’t yet seen one with the combination of widespread impact and severity on a par with natural disasters and pandemics. From a technology and business models perspective, we are still in the early days of Systemic Dependency Risk, and we shouldn’t expect there to be a robust historical record from which to draw statistics. But we’ve seen enough early warning signs that, with a little imagination, we shouldn’t have to find ourselves completely taken by surprise when “the big one” happens.

Taking earthquakes as an analogy, suppose as a thought experiment that the Earth had not been seismically active until about 30 years ago… an event like the 1906 San Francisco earthquake might be “unprecedented” relative to the 1995-2025 historical record, but you would like to think that with the record of smaller earthquakes over that period and geological analysis, seismologists would have enough talent and imagination to suppose that a magnitude 7+ Bay Area quake could plausibly happen with a sufficient likelihood to merit attention from risk managers.

Many of the hazards we model don’t even have reliable historical observation periods nearly as long as the return periods we care about. North Atlantic hurricanes in the US southeast weren’t recorded prior to denser settlement in the late 1800s and even then, it wasn’t until the advent of radar, satellite imagery and hurricane hunter aircraft all within the past 100 years that we were able to gain robust data for hurricanes prior to landfall. NOAA’s hail records go back less than 100 years, and even then they are subject to severe observation bias in sparsely populated areas prior to the past two or three decades. And while paleo-seismology offers some indications of earthquake history stretching back thousands of years, prior to the invention and deployment of seismographs over the past 100 years, older historical earthquake magnitudes have to be estimated based on severity and extent of impacts.

It’s always an uphill battle to convince people to worry about risks that lie beyond the frame of reference of their personal experience, even when we’re talking about probability thresholds like 1-in-100, 1-in-250, 1-in-500, etc. that explicitly do lie beyond the experience of a typical human lifespan. Often when risk modelers talk about the extreme scenarios that make up the tail just beyond those risk thresholds, we are met with a reaction something like “that’s too extreme – nothing like that has ever happened before”. To that I always say:

500 years is a very long time

When someone says the 1-in-100, 1-in-250, 1-in-500 scenarios are too extreme (or “unprecedented”?), I offer up the following partial list of truly extreme events that have happened in the past 500 years:

- Two severe global pandemics approximately 100 years apart: the 1918 Spanish Flu and COVID-19

- The 1908 Tunguska asteroid impact

- The 1700 Cascadia Earthquake (estimated magnitude 8.7-9.2) for which there is no contemporaneous historical written record, other than The Orphan Tsunami of 1700 which was recorded in Japan without a corresponding earthquake

- The Great Lisbon Quake of 1755 (estimated magnitude 8.5-9.0), which triggered a firestorm in Lisbon from knocked over candles lit for All Saints Day, as well as a tsunami possibly 5m high in Lisbon and over 10m high along the coast of Portugal, and also recorded in England (3m high), France, Newfoundland, the Caribbean, and Brazil

- “The Year Without Summer” in 1815 was a volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mt. Tambora, with major global impacts including a disrupted monsoon season and major floods in Asia, crop failures in England which contributed to the “Bread or Blood” riots and similar in Continental Europe, crop failures in the US Northeast that may have driven westward migration… and a similar event happened just 32 years earlier when the 1783 Laki eruption caused a poisonous sulfur dioxide cloud to blanket Western Europe, followed globally by a cool summer and a severe winter

- The Carrington Event in 1859 which is the strongest geomagnetic storm ever recorded, causing electric shocks and fires from induced current in telegraph lines and railroad tracks

The past 500 years have also seen plenty of bizarre but less catastrophic events such as 1858’s Great Stink in London (rather amusing, in contrast to the very deadly Great Smog of London in 1952) and the Great Kentucky Meat Shower of 1876 which stands out from the surprisingly much more common occurrence of storms raining tadpoles, fish or other animals). The box at right lists 9 instances of alcoholic and/or edible floods over the past two centuries, which are amusing but for several of them causing fatalities.

Alcoholic and/or Edible Floods

- The London Beer Flood of 1814*

- The Dublin Whiskey Fire of 1875*

- The Great Gorbals Whiskey Flood of 1906*

- Boston’s Great Molasses Flood in 1919*

- Also in 1919, a chocolate flood in Brooklyn caused by a fire at Rockwood & Company

- Albany Molasses Flood of 1968*

- A flood of melted butter and cheese from Wisconsin’s Great Butter and Cheese Fire of 1991

- The 2017 Pepsi Fruit Juice Flood in Russia

- The Levira Distillery wine flood in Portugal in 2023

* fatalities involved; see data table for more details

There have also been at least two notable “unprecedented” strings of major catastrophe events over short periods of time in just the last 35 years.

From 1991 to 1995 we had major landmark events for almost every kind of natural disaster you can think of:

- Oakland Hills wildfire in 1991

- Mt. Pinatubo eruption in 1991

- Hurricane Andrew in 1992 making landfall as a Cat 5 in Florida

- The Great Flood of 1993 along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and The Great Blizzard of 19935

- The Northridge earthquake in 1994 (Mw 6.7)

- The Kobe earthquake in 1995 (Mw 6.9)

In 2004 and 2005 we had seven major US landfalling hurricanes:

- Charley (Cat 4)

- Frances (peaked at Cat 4… Cat 2 at US landfall)

- Ivan (peaked at Cat 5… Cat 3 at first US landfall)

- Jeanne (Cat 3)

- Katrina6 (peaked at Cat 5… Cat 3 at New Orleans landfall)

- Rita (peaked at Cat 5… Cat 3 at TX/LA landfall)

- Wilma (peaked at Cat 5… Cat 3 at US landfall)

And in the winter between those two hurricane seasons, we had the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami caused by a Mw 9.2 earthquake off the coast of Indonesia.

…so, when it comes to envisioning the possibility of extreme Systemic Dependency Risk events, I’ll remind everyone that we’ve had at most only a couple of decades historical experience in anything resembling our current globalized economic system and business models, and 500 years is a very long time. We need to extend that sparse history with some imagination so that we don’t find ourselves unprepared and calling the first big Systemic Dependency Risk event “unprecedented”.

- That 2.25x range matters a lot when you think about the implications for mass and potential energy – closer to a 10x difference. ↩︎

- If you need a new extremely low probability / high severity scenario, apparently there is a 0.2% chance over the next 5 billion years that a passing star could cause Mercury to collide with Earth or eject it out of orbit. ↩︎

- Bearing in mind that impacts near enough to a major inhabited area, including ocean impacts causing a significant tsunami, could still be devastating. ↩︎

- One other unusual feature of asteroid impacts in comparison to other natural disasters is lead time. After initial observations, the probability of striking Earth is eventually revised to 0% or 100% long before impact (e.g. Asteroid 2024 YR4‘s impact would have been 2032), eventually including a fairly precise estimate of the impact location. There will be plenty of opportunity to mitigate some of the risk (perhaps including government attempts to “nudge” the trajectory), even if assets in the impact zone have to be written off. ↩︎

- Both of which may have been indirectly influenced by the Mt. Pinatubo eruption. ↩︎

- I will allow that the flooding in New Orleans caused by Katrina, and the subsequent population displacement and regional economic impact, do properly qualify as unprecedented. ↩︎

Leave a comment