A company’s dependency risk is the possibility that some asset or service outside of its control ceases to function properly, causing a disruption to its ability to conduct business, including manufacturing goods, operating services, selling its products or services, or any other activity without which the company faces adverse financial consequences. Dependency risk obviously includes suppliers, but also may include public infrastructure, logistics, communications, third party software-as-a-service, cloud computing, outsourcing, payment systems, etc. You might think of this as a very broad or expanded version of supply chain risk, or more strictly you might think of supply chain risk as an important subset of dependency risk.

This more expansive version of supply chain risk is an important shift of thinking that reflects our modern economy with business models that have trended towards services rather than manufacturing, are increasingly vertically disintegrated and part of networked ecosystems, and in any case are more dependent on technology solutions in almost every aspect of the business. Making matters more challenging, the straightforward approach to identifying supply chain risk through payables and vendor management won’t necessarily catch these modern versions of dependency risk that might be based on revenue shares or mutual benefit in an ecosystem model.

Following are a few examples of dependency risk that fall outside of traditional supply chain risk:

- port and/or shipping route disruption (e.g. congestion at Port of Long Beach, Port of Baltimore closure due to the collapse of the Francis Scott Key bridge, the Ever Given running aground and blocking the Suez Canal, Maersk’s NotPetya infection causing closures at ports it operated)

- unavailability of key Software-as-a-Service (e.g. ransomware attack on CDK Global which many auto dealers rely on for sales management and/or service scheduling)

- disruption of GPS signal for rideshare apps, automated farm machinery and transportation systems

- unavailability of online marketplaces (e.g. eBay, amazon.com, etc.) for smaller retailers

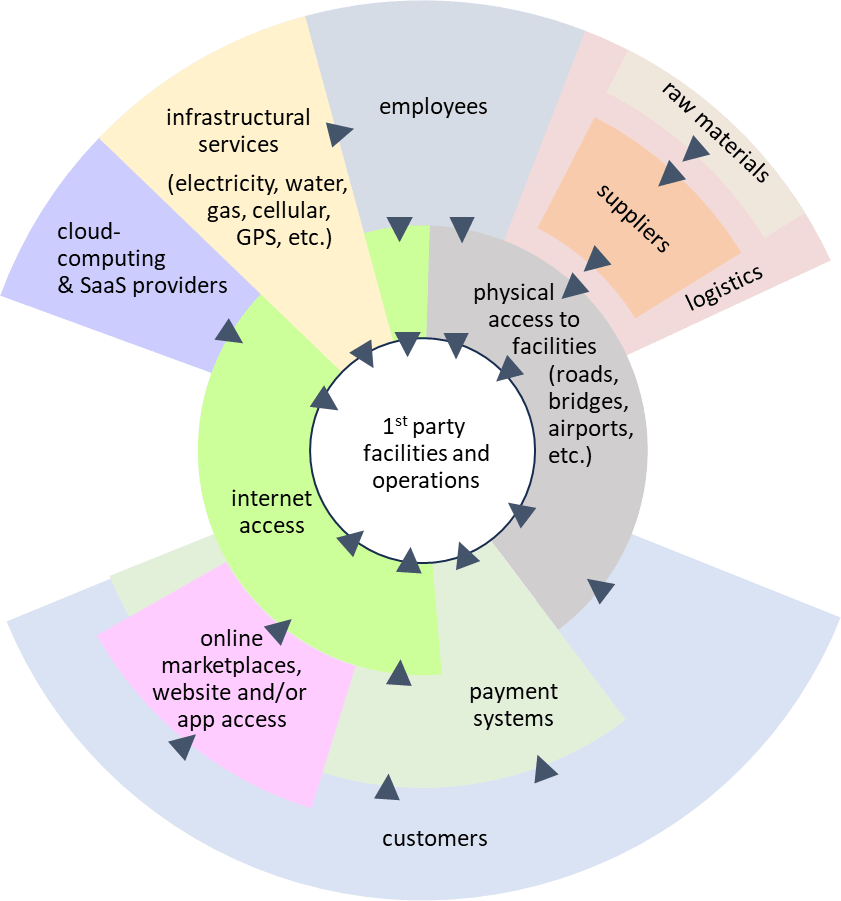

The variety of dependencies beyond the traditional supply chain are illustrated for a generic business in the diagram below. The top half depicts the inputs required to generate the products and/or services this business provides. Note that many of the dependencies have their own dependencies, such as logistics transporting raw materials and components throughout the supply chain. And critically, all of the inputs need to arrive at the business, which is dependent on either physical or internet access. Similarly, the bottom half follows the revenue cycle by which customers need to have the means to buy the products or services and for the business to then obtain payment.

Any given business will face its own specific configuration of dependencies which may be a subset of the categories in the diagram, as well as other dependencies not included for this generic business. Once specific dependencies are fully identified, it’s probably more helpful to think of individual dependencies rather than categories in chains forming more of a web-like diagram.

So why then do we care about *systemic* dependency risk? Systemic Dependency Risk is simply the case where many companies have the same dependency such that a failure could have widespread economic ramifications and knock-on effects. It then becomes an important risk from a public policy perspective and a potential vector for “correlation” in loan and/or equity portfolios. In a worst-case scenario, a Systemic Dependency Risk event could potentially cascade unpredictably and chaotically into secondary Systemic Dependency Risks.

Non-systemic dependency risks – where only one or a few companies are at risk to a failure of the dependency – are more readily controlled or mitigated. For suppliers and technology providers, a company might consider an array of tools: contracting provisions, lining up contingent or redundant providers, or even vertical integration. Private-public partnerships could also be a tool in the case of infrastructure dependencies, for example if a company’s operations are uniquely dependent on a particular road, bridge or airport such that it might make sense to fund resilience improvements to mitigate the risk.

The other reason we care about Systemic Dependency Risks is that they are often too hot to handle for the insurance industry, similar to large natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes in heavily exposed regions like Florida and California. Lack of insurance options is a risk management problem both for individual companies and the economy as a whole, as well as a loss of valuable “cost of risk” signals for decision-making. We’ll dive deeper on the insurability angle in a future post.

One subtle aspect of Systemic Dependency Risk is that it’s neither a peril-oriented or insurance product-oriented view of risk – we care about the unavailability of some critical service, asset, input, etc. and don’t care particularly much about what caused that unavailability. The Systemic Dependency Risk examples we’ve discussed are all consequences of an underlying peril (e.g. ransomware for the Colonial Pipeline disruption as well as the NotPetya-Maersk port closures, potentially a geomagnetic storm for GPS signal disruption, etc.) which is an important distinction when we think about insurance solutions. Peril-oriented modeling starts with the characteristics (location, magnitude, etc.) and corresponding frequency of some exogenous event, like an earthquake or hurricane. From there, the event is mapped into a local hazard intensity (e.g. maximum wind speed at a particular location in a hurricane) of an exposure of interest, and then via damageability functions relating hazard intensity to the financial impact for that exposure. Of course, from a would-be-insurer perspective, it is important to consider the underlying perils that might cause a disruption event, and particularly how that might aggregate with other exposures to that peril (e.g. infrastructure disruption caused by an earthquake that also causes large losses under traditional property damage insurance).

Similarly, insurance products are organized around categories of loss (e.g. property damage, third-party liability, etc.). Consequently, the underlying perils that drive those losses are generally aligned to the products (e.g. natural disasters generally cause property damage), though there are some cases of potential cross-over such as workers comp losses in an earthquake. Business interruption is typically a secondary coverage for some policy types (e.g. property, cyber), which then also carries through the linkage to underlying perils.

But from a policyholder perspective, it doesn’t really matter (all else equal in terms of duration and severity of the disruption) what product category a dependency risk that has caused a disruption belongs to, and it is challenging to manage that risk with a partial patchwork or peril/product-oriented coverages across multiple polices.

And it’s largely because it doesn’t fit the peril-based modeling and product/coverage-based insurance frameworks that Systemic Dependency Risk requires us to think about new tools and approaches to modeling and managing this risk.

Leave a comment